ARTICLE 11: DCTs-new kid on the block or a venerable idea resurrected?

In the eleventh article of our series of articles on Managing Data and eClinical solutions for Medical Device Companies, the CRFWEB team takes a slightly sideways take on the current enthusiasm for Decentralized Clinical Trials. Much has been written on this topic since the start of the Global Pandemic, but this is hardly a new idea, and hardly one without complex and challenging issues.

We will look at the critical role EDC will have supporting DCTs and what key issues need to be addressed still to ensure that they deliver safe, compliant high quality data over the full product life cycle.

We’ll also explore the challenges and opportunities presented by the wider adoption of Decentralized Clinical Trials.

This article will take a closer look at:

- The fascinating origins of DCTs

- The problems with the traditional RCT model and the ways in which modern DCTs may overcome them

- The challenges that need to be met to ensure that DCTs deliver safe, comprehensive and compliant data for Clinical Trials

“…need (the mother of all inventions) taught them.”

Thomas Hobbes, Leviathan, 1651

Many eClinical vendors have, over the last two years, posted valiant accounts of how they have gone all out to develop technologies to support Decentralized Clinical Trials (DCTs). As pharma, biotech and medical device companies have grappled with conducting clinical trials under the constraints of the global pandemic, Necessity as the Mother of Invention has become the standard, if somewhat self-congratulatory trope for describing this trend. All well and good, but Necessity here is surely less the Mother of Invention and more the slightly exasperated school teacher no longer prepared to accept that the dog ate the homework. Again.

How do DCTs contrast with the more traditional RCTs? For while it’s true that RCTs have long been seen as the gold standard, they have never been unblemished by criticism. RCTs have always been open to charges of artificiality – that studies don’t adequately reflect in their design likely real-world use and that study cohorts are often not fully representative of the potential patient population. RCTs are also notorious for being slow, resource-intensive and expensive.

RCTs have traditionally been based at a number of clinical research sites, usually academic medical centres, hospitals or GP practices. The sites are paid by Pharma, Biotech or Medical Device Companies to recruit, enrol, treat and monitor trial participants; however, they will only have access to a limited number of patients with a condition relevant to the study. Enrolled subjects will need to visit the site regularly for study visits, which can be difficult for many people; data suggests that some 70% of drug trials fail to recruit their target population and ensure adequate adherence to the trial protocol. Unsurprisingly, then, this has meant that for many trials that have taken place in the US and Europe, white, male and relatively well-off people have been historically over-represented in study cohorts. The potential danger of this structural bias was highlighted recently when serious concerns were raised that pulse oximeters might be dangerously inaccurate for some patients from ethnic minority communities, and which could have led to people not receiving appropriate care for Covid-19. In November 2021, The UK Health Secretary, Sajid Javid, ordered a review into the efficacy of such devices.

“That’s an excellent suggestion, Lady Montague*. Perhaps one of the men here would like to make it?”

With apologies to the cartoonist, Duncan

So, there is a rich irony about the recent enthusiasm for DCTs. DCTs, in contrast to the traditional RCT model, are trial protocols that seek to explore the impact of a medical treatment in the patient’s natural environment by ensuring that as many trial activities as possible can be conducted during their normal, day-to-day lives, rather than during a visit to the clinical trial site. Far from being the great new saving idea, decentralization is as old as the concept of the controlled medical trial. In 1747, the English physician, Dr James Lind, conducted an onboard nutritional experiment with crew on board the Royal Navy ship The Salisbury, to see if he could identify a successful way of preventing scurvy, then one of the many afflictions that plagued the lives of sailors. He compared 6 different nutritional interventions and as a result, identified citrus fruits as providing the missing dietary component that stopped this horrible disease from developing. That much is well known and explains why this is a well-referenced Origin Story for DCTs. A further irony, though, is that this “fair test”, as he called it, is rather hidden away and occupies just four pages, unmarked by a subheading, in his 450-page book, A treatise of the scurvy. Far from being the “Eureka” moment of legend, this was just one idea among many in what is a very long, difficult and often self-contradictory work. Plus Ca Change? Not really, great new ideas are not often fully realised at the time. They rarely soar above the status quo and when they try to take wing, there’s almost always a desperate battle for visibility – a grisly fight to overcome the damning and dismissive opinions of the lofty disparagers who have much to lose when paradigms shift.

*Lady Mary Montague introduced inoculation in England in 1721, successfully inoculating her own daughter, decades before Dr Edward Jenner used live cowpox to achieve the same feat. Lady Montague had learned of the procedure in Turkey, where it had been used for centuries.

Q: How many Oxford Dons does it take to change a light bulb?

A: Change…CHANGE!??

It’s interesting to consider, too, that the highly institutional structure of most RCTs may also have been a problem in itself. In recent years it’s become increasingly clear that academic research publications are overly biased toward the reporting of studies that demonstrate a degree of benefit. Too often such benefits have been so marginal that they have proved all but impossible to replicate. Negative or inconclusive studies have tended to suffer the inglorious fate of “file and forget”. Institutional reputation is founded on published research and while fraud is still mercifully very rare, few would disagree that there are genuine structural concerns about how medical research is conducted and reported that we are only now coming to terms with.

Institutional inertia can impede the urgency to act. Medical Science tends to be extremely conservative, a quality for which we should all be grateful. Scepticism is an important bulwark against quackery and greed; the need to prove there is a better solution to a problem before it is widely adopted is what keeps us safe. In reality, conservatism also means that harmful, or at best, pointless practices persist beyond conclusive evidence that they should be consigned to the museum of grisly medical horrors. As evidence, I offer the Lobotomy, a medieval procedure that never had any sound medical justification, but which persisted up until the late 1960s and, more prosaically, the Tonsillectomy, still carried out today despite an absence of evidence of its efficacy.

Institutional inertia also simply protects those vested in the status quo. Medical academia, healthcare companies, competent authorities, CROs, EDC/CTMS vendors etc. all understand the traditional model, and their role in it. Many make lots of money, too. Change means new pathways and processes need to be mapped, validated and regulated; new products and services to be developed, tested, verified and adopted. Change is expensive and change always offers an opportunity for new players to challenge the incumbents. You can see why the medical-industrial complex would drag its collective feet; it’s taken a pandemic to force a rethink.

“Never Waste a Good Crisis”

Andrew Wolstenholme, 2009

However, when change is inevitable and unavoidable, we have an economic model that works very, very well to deliver new products and services. Healthcare is one of the great growth industries of the early 21st century and healthcare technologies are, in particular, the focus of an investment goldrush. The last two years has seen a blossoming of new platforms designed to meet the needs of DCTs, and existing players working hard to adapt their offerings, too.

DCTs are not a universal panacea and they do have their own significant challenges to meet. Not least the following issues need to be addressed:

- How can “technology access” bias be successfully mitigated? Is subject variability limited by access to quality Wi-Fi, tablets and smartphones going to a problem? How can it best be dealt with?

- Throwing the baby out with the bath water. Designing studies that minimize or even remove reliance on trial sites could mean that subjects that need help from medical staff would struggle to adhere to the protocol, and could lead to costly delays and even failure. Getting the balance right is critical.

- Ensuring privacy and security. There’s no doubt that breaches of privacy and security are inherently more of a concern with DCTs. Great care needs to be taken to ensure that the technology solution adheres to all the required standards as demanded by the local Competent Authority and that the protocol is strongly interrogated to ensure that it does not introduce unexpected vulnerabilities.

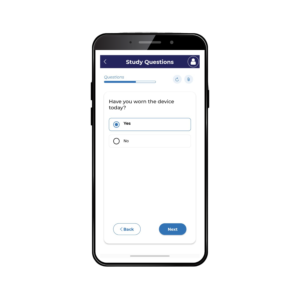

- Adapting to new technologies. Care needs to be taken that medical staff as well as subjects fully understand the technology and its use. Training and support need to be well designed and easily accessible

- Protocol deviations. Standard RCTs do tend to ensure that research protocols are followed precisely. For some more complex trials, patients sending in data unsupervised can lead to many more errors. This awareness needs to be an explicit and fundamental design consideration. It may be that patients may be able to visit the nurse at their GP or go to a local pharmacy when they need data recorded.

- Designing for variability. Collecting data from patients at different times when they may be in different places and under differing stresses and strains offers fantastic potential for better understanding how a drug or device might perform in real life. Patient data might vary greatly depending on these factors and a protocol will have to be able to take this into account and not for example issues alerts if a variable is outside of an expected range, without taking into account the immediate context – this is not a trivial concern.

- Data overload. The amount of data coming in – especially if wearables are in use – can be overwhelming. The costs and complexities of data management might mean that DCTs can quickly become more onerous and costly than traditional RCTs. Technologies need to be in place that can collect and organize data automatically. Again, this needs to be a foundational consideration for the protocol design.

DCTs will no doubt be supported by rapid technological innovation, but their value will be delayed and perhaps even diminished by players in the clinical trials ecosystem being slow to adapt their underlying assumptions and their ways of working. This is particularly true of those in the regulatory sector. The promise of DCTs is real, though, and if we can overcome these obstacles, we just might be witnessing the dawn of a new Golden Age in clinical research.

How Clindox can help you

Clindox has a natural advantage over many of our competitors as we can leverage the benefits of:

– Long established, low cost-base development and support centres of the highest calibre

– High degree of sponsor self-sufficiency for study builds (with cost-effective client onboarding processes and expert support as required)

– Solution stack delivered through a simple, flexible SaaS model

Objectively, cost-plus – the true driver obscured by the smoke and mirrors of pricing plans – favours our offer and to this end you will find our proposals will be far simpler than any of our competitors and notable by the absence of arbitrary, hard-to-justify significant variability.

All in all, we know that with our low cost-base and our ongoing commitment to self-sufficiency, simplicity and transparency, we will always provide an excellent value proposition without compromising on features or quality… whichever sector you’re from, and whatever your study or investigation needs are.